For a change, no H0 tension in this week’s entry (although I briefly touch on a new H0 measurement in paper 1)! This week I cover a new way to measure cosmological distances, a new dark matter candidate from an alternative to black holes, and the first calculation of how the neutrino Casimir force depends on the Dirac vs Majorana nature of neutrinos. Enjoy, and stay at home!

#1 2003.10278: Using variability and VLBI to measure cosmological distances by Jeffrey Hodgson et al.

One of the most important breakthroughs in the past century which led to the establishment of the standard model of cosmology (LCDM), including the discovery of cosmic acceleration, has been our ability to probe distance scales way beyond our local neighborhood. More precisely, our ability to probe the distance-redshift relation well into the Hubble flow (see the Wikipedia Cosmic distance ladder page for a complete discussion). For example, you might certainly have heard about standard rulers, standard candles, standard sirens, and so on: these are all distance indicators which are based on some well-known intrinsic property of an object/class of objects, the distance to which one can then estimate by comparing the observed apparent property with the known intrinsic property (recently with Cosimo Bambi and Luca Visinelli we studied a proposed standard ruler using BH shadows in 2001.02986). You actually use standard rulers every day, when you estimate the distance to a person by comparing the person’s apparent height to their known height! Needless to say, given the extremely important conclusions one can draw by measuring the distance-redshift relation (testing gravity, curvature, cosmic acceleration, the Etherington duality, new physics beyond LCDM, and so on), it is highly desirable to find novel and independent ways to measure this relation and cross-check for systematics in previous measurements. The first to attempt to use active galactic nuclei (AGNs) as standard rulers as performed by Gurvits et al. in 1999, with little success.

In this week’s paper, Hodgson et al. propose what as far as I know is a new way to use AGNs as standard rulers, using the speed of light to calibrate the ruler. Given a certain AGN observed either as a radio galaxy or a blazar (depending on whether the jet axis is close enough to being aligned with our line-of-sight), one can measure the angular size of the AGN via very-long-baseline-interferometry (VLBI). On the other hand, AGNs are known to exhibit strong variability on a wide range of wavelengths and timescales. One such timescale is related to the time difference between the minimum and maximum flux density during a flare in the source. One can then infer a physical scale from this timescale (basically multiplying it by the speed of light, and then correcting for the redshift of the source), and the ratio between this physical scale and the VLBI-measured angular scale is the angular diameter distance to redshift z. Hodgson et al. then go on to concretely apply the method to the bright radio core of the Perseus cluster, and manage to measure the angular diameter distance to the source, as well as the Hubble constant (which they find to be approximately 73±5 km/s/Mpc). This paper is a very interesting proof-of-concept, as it is totally independent of any cosmological assumption and in principle can be applied to non-AGN sources. On the other hand, one is trading cosmological assumptions for astrophysical ones (which are usually much “dirtier”). The assumption that the variability velocity can be approximated by the speed of light seems to me a reasonable one (since the flare emission comes from synchrotron emission from electrons). What is critical for this method to work is a precise estimation of the variability timescale, and this is where systematics can creep in: for instance, how exactly do you define a flare? What is the best way to determine this timescale? One thing which wasn’t 100% clear to me is whether the particular flare timescale chosen by Hodgson et al. is “typical” (in other words standard/standardizable) and can easily be identified in other AGNs, given how these vary on a wide range of timescales (which also depend on the observation wavelength). I expect these and other issues will be addressed in follow-up papers further discussing this method, which I look forward to reading.

#2 2003.10682: Not quite black holes as dark matter by Ufuk Aydemir, Bob Holdom, and Jing Ren

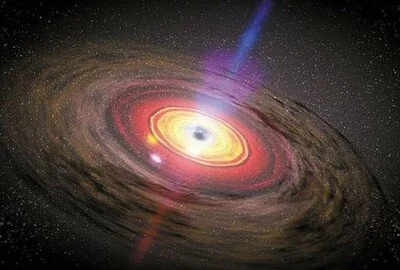

The past years have seen a renewed interest in primordial black holes (PBHs) as dark matter (DM), spurred by the recent gravitational wave (GW) detections by LIGO, and by two well-known papers (1603.00464 by Bird et al. and 1607.06077 by Carr et al.). On the other hand, PBHs do not necessarily arise in a “natural” way, and do not seem to bring us any closer to addressing the BH information paradox (BHIP), so it is perhaps desirable to try and find a way to kill two birds (DM and the BHIP) with one stone (some beyond-GR compact object?). In fact, in recent years, evidence has grown in support of the observation that a resolution to the BHIP might require new physics at the gravitational radius (i.e. at the horizon scale) rather than at the Planck scale (with Cosimo Bambi, Katie Freese, and Luca Visinelli we studied one such modification in light of the Event Horizon Telescope image of M87* in 1904.12983). One serious possibility is that some new physics might halt gravitational collapse, to the point that one is left with a horizonless ultracompact object. Being there no event horizon, there is no BHIP to begin with! Presumably these objects should then evaporate, and the same new physics might halt evaporation and leave a remnant behind, which might be a suitable DM candidate. But is there a sensible theory where objects with these characteristics arise naturally?

The answer, as Aydemir and collaborators study in this week’s paper, is yes! The underlying theory is quadratic gravity. Quadratic gravity is perhaps the most motivated extension of General Relativity. In quadratic gravity, one adds all quadratic curvature terms on top of the Einstein-Hilbert term. This leads to a theory which is renormalizable, and there is strong evidence that it might also be asymptotically safe (I think a formal proof is still lacking), which make it an excellent candidate theory of quantum gravity. In quadratic gravity, a compact matter distribution doesn’t necessarily lead to the formation of a horizon, and the end product of gravitational collapse can be a so-called 2-2-hole (see 1612.04889), so called because the metric vanishes as r^2 when approaching the origin. Primordial thermal 2-2-holes will radiate the same way PBHs do, but at a certain point evaporation halts and what is left behind is a cold, stable remnant with a minimal mass determined by the spin-2 mode of quadratic gravity. This new spin-2 mode is introduced by the contraction of the Weyl curvature tensor with itself in quadratic gravity. Aydemir and collaborators then go on to show that remnant 2-2-holes can account for all the DM while satisfying all observational constraints. The most striking signatures of 2-2-holes would come from the merger of 2-2-holes. These would merge into a non-remnant state, which in turn would produce a strong emission of photons and neutrinos before settling back into a remnant state. Constraints from high-energy photon and neutrino fluxes therefore set very stringent constraints on the minimal mass of 2-2-holes, which the authors find should be less than 10 times the Planck mass. The minimal mass is directly related to the fundamental parameters of the theory, and this stringent constraints seems to point towards the attractive feature of a theory of quantum gravity with only one fundamental scale, i.e. the Planck mass. There hasn’t been much work done on 2-2-holes but, with recent developments in GW and VLBI technology which are pushing towards tests of gravity in the strong-field regime, I think it is definitely worth studying these objects further. For instance better understanding GW echos produced by 2-2-hole mergers, or studying the shadows these objects cast - it is not necessary to have a horizon to cast a shadow, in principle all that is needed is an unstable photon sphere.

#3 2003.11032: The Neutrino Casimir Force by Alexandria Costantino and Sylvain Fichet

Are neutrinos their own antiparticle? In other words, are they Dirac or Majorana fermions (the answer to the previous question would be “no” and “yes” respectively). This has been one of the biggest questions in neutrino physics since these elusive particles were first discovered. The reason why it is so hard to distinguish Dirac vs Majorana neutrinos is known as the “Majorana-Dirac confusion theorem”, which amounts to the statement that for relativistic neutrinos (with p>>Mnu, where p and Mnu are their momentum and mass respectively) the results of experiments are not sensitive to the mass generation mechanism (this is a property of the Standard Model, and introducing gravity breaks this theorem, although it is still very hard to exploit this, see e.g. 1908.03286). Perhaps one of the most promising ways to address this question is to search for neutrinoless double-beta decay, which can only occur if neutrinos are Majorana. Going back to the Majorana-Dirac confusion theorem, its result relies on the assumption p>>Mnu, so one of the ways to circumvent this theorem would be to go into the opposite regime. This, however, is challenging since we know that Mnu~0.1 eV from cosmology in combination with oscillation experiments, an energy range which is way out of reach of most scattering experiments. If you recall from your quantum mechanics courses that p~1/λ, with λ a typical wavelength/distance, another way to evade the confusion theorem is to move to long distances λ>>1/Mnu, and study macroscopic forces due to exchange of virtual neutrinos. A recent application of this idea was performed in 2001.05900 by looking at pointlike sources. However, perhaps more relevant for concrete experiments is the neutrino force between extended objects, given that the neutrino Compton wavelength is at least a micron, much larger than the atomic scale.

In this week’s paper, Costantino and Fichet fill this gap by studying the neutrino Casimir force between two plates, or between a plate and a point. They perform a careful computation of the potential between the sources, and then compute the relevant Casimir force. It is the first time this interesting calculation is performed in the literature. All results in the paper are conveniently written in terms of a parameter eta, which is =1 for Dirac neutrinos and =0 for Majorana neutrinos, so all the results are written in an unified way and the reader can easily see where the differences between the two mass generation mechanisms enter in each and every calculation step. The most useful visual representation of the results is given in Fig. 3, which plots the ratio of the Dirac to Majorana potentials as a function of the product λ×Mnu, recall that the confusion theorem applies for λ×Mnu<<1. As one sees from the figure, this ratio approaches 1 in the regime where the confusion theorem applies, and drops to zero in the opposite regime, consistent with previous results that the force due to exchange of Majorana neutrinos is always weaker than its respective Dirac counterpart (see e.g. hep-ph/9606377, although I don’t know if there is a heuristic explanation for this, other than it follows from the different form of the effective 4-fermion Lagrangian density). Are we any close to distinguishing Dirac vs Majorana neutrinos using quantum forces? Unfortunately, as discussed in the conclusions, current sensitivity is still orders of magnitude far from being able to make such a distinction.