This week’s post covers ultralight axions and galaxy clustering, using heavy elements to probe inelastic dark matter, and constraining primordial black holes from the dynamics of Neptune. Enjoy!

#1 2104.07802: Constraining Ultralight Axions with Galaxy Surveys by Alex Laguë et al.

Axions are well-motivated light particles, initially proposed to solve the so-called strong CP problem, i.e. why does the QCD sector of the Standard Model (SM) not violate charge-parity symmetry - or the related question of why is the neutron dipole moment so small? While the QCD axion is typically expected to have a mass in the ~µeV scale, lighter axions generically appear in extensions to the SM. In fact, they are expected to be ubiquitous within string theory, which appears to predict the existence of a so-called string axiverse (see hep-th/0605206 and 0905.4720): a plethora [O(100)] of ultra-light axions (ULAs) spanning a wide mass range, with logarithmically distributed masses. Axions from the string axiverse may behave as either dark matter (DM) or dark energy (DE) - the latter if they are lighter than ~10^-33 eV - and a particular range of ultra-light axion masses around ~10^-22 eV, usually termed fuzzy DM (FDM), is of interest for the possible small-scale crisis of the cold DM paradigm (if you believe such a crisis is there in first place). Many of the authors of this week’s paper such as Hložek, Marsh, and Grin, have searched for ultra-light axions in CMB data: see e.g. 1410.2896 and 1708.05681.

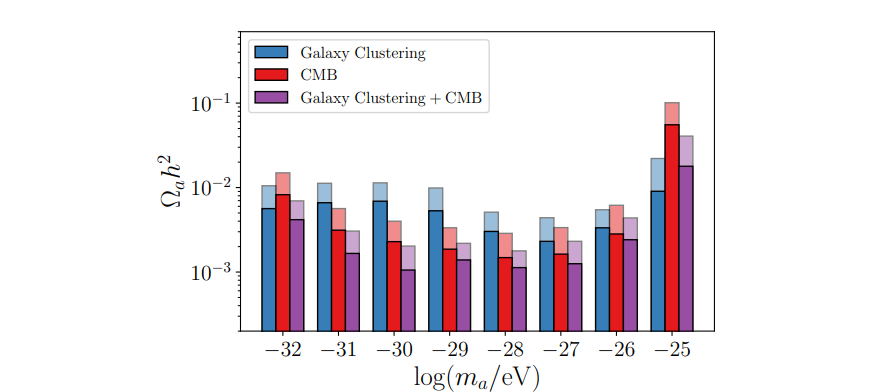

In this week’s paper, they take the next natural step, i.e. to constrain ULAs composing a fraction of the DM using galaxy clustering measurements from the BOSS survey (monopole and quadrupole of the BOSS DR12 CMASS and LOWZ samples). Doing so required several highly technical steps, including testing the validity of the effective field theory of large-scale structure in the presence of a mixed ULA-cold DM scenario, developing a “smart” interpolation scheme for efficiently computing the axion contribution to the matter power spectrum, and so on. In the analysis, the axion mass is not varied as the usual parameters, but is fixed in 8 bins evenly spaced in logarithmic space between 10^-32 eV and 10^-25 eV, whereas what is varied is energy density in axions - the reason was better explained in the earlier papers I linked above, but if I recall correctly it has to do with a nasty degeneracy between mass and energy density which would make it tricky to vary both together. The key results of the paper is shown in the plot below - basically the axion energy density contribution has to be very small across the whole mass range, and in particular <0.004 (i.e. no more than 5% of the DM) in the range between 10^-31 eV and 10^-26 eV. Exact numbers aside, the main general important message of this paper is that galaxy clustering has really got to the point where it has a comparable constraining power to the CMB (potentially even stronger) for many interesting models, though it does come with added theoretical modeling difficulties.

Addendum: I recently saw somewhere on Twitter (can’t remember who wrote this) that the first author, Alex Laguë, will be on the postdoc job market this year, in case that might be of interest to anybody reading this who will be hiring postdocs later this year. I treat Twitter info as being public domain, with the usual not-100%-accuracy warning (which also applies to the Rumor Mill).

Credits: Laguë et al., arXiv:2104.07802

#2 2104.09517: Closing the window on WIMPy inelastic dark matter: journey to the end of the periodic table by Ningqiang Song, Serge Nagorny, and Aaron Vincent

Most DM direct detection (DMDD) experiments are appositely designed to probe WIMP-like particles with ~GeV-TeV mass and weak-scale interaction cross-sections (~10^-40 cm^2), by searching for the signatures of DM recoiling off heavy nuclei, with the target nuclei kinematically matched to be sensitive to WIMPs with ~10-100 GeV masses. Well-known target nuclei in this context include Xenon and Germanium. However, we really only know the density of dark matter, both in the local neighborhood and on cosmological scales, so this doesn’t really tell us anything about its mass or kinematics - exploring the “weak” range, at this point, is mostly a matter of theoretical prejudice (or so I’ve always thought). As DMDD experiments are slowly closing in on the window of possible WIMP candidates in the GeV range, it is important to explore other possibilities in model space. One interesting possibility is so-called inelastic DM (IDM - not to be confused with the famous Identification of Dark Matter conference!), a class of models invoked among the others to explain various possible experimental anomalies

In its simplest incarnation, IDM features two DM states: one light state dominating the relic abundance, and one heavier one, with two-to-two scattering processes with baryons exciting or de-exciting the DM state. Clearly, to overcome the mass splitting, there is a kinetic energy threshold which must be reached, which in turn sets a minimum threshold for the relative velocity or exchange momentum such that the DM-baryon interaction can occur. Importantly, this means that if the target nuclei are sufficiently light, or the analysis is only sensitive to low recoil energies, IDM is kinematically suppressed [see Eq.(7)] and can evade DMDD searches. Motivated by this and in search of better ways to constrain IDM, or rather to probe larger splittings, in this week’s paper Song and collaborators turn their attention to heavier target nuclei - thus the journey to the end of the periodic table, though not to the very end (where the most exotic elements live).

This week’s paper essentially considers two detection channels for IDM which make use of heavier nuclei. The first is the classical recoil channel due to high momentum-transfer coherent DM-nuclei interactions. The second is instead nuclear excitation from interactions with IDM - the subsequent nuclear decay or de-excitation leads to gamma-ray photons which then appear as an excess over the known background. For the first channel, the compounds CaWO4 and PbW04 (calcium tungstate and lead tungstate respectively) are considered. For the second channel, the 201 isotope of Mercury, alongside more exotic elements such as Osmium and Hafnium, are considered, in the context of searches for rare decays. Making some (reasonable) assumptions on the DM velocity distribution, the results are shown in the figure below, which clearly shows that the search proposed by the authors is able to probe mass splittings of up to ~600 keV, larger than ever explored in the literature, while it is expected that future experiments will be able to significantly improve existing constraints. Overall, an interesting paper which goes beyond the reach of “classical” DMDD experiments!

Credits: Song, Nagorny & Vincent, arXiv:2104.09517

#3 2104.07672: Constraining Primordial Black Holes Based on The Dynamics of Neptune by Amir Siraj and Avi Loeb

The orbital eccentricity of a planet (or any astronomical object in general) measures how much its orbit deviates from that of a perfect circle. For a perfectly circular orbit the eccentricity is e=0, whereas 0<e<1 for an elliptic orbit, e=1 for a parabolic orbit, and e>1 for a hyperbolic orbit. Of the Solar System’s planets, Mercury is the one with the largest eccentricity (e~0.21), while this record previously belonged to Pluto (e~0.25), prior to its demotion to dwarf planet. Venus, on the other hand, has the lowest eccentricity (e~0.007). Short of that, Neptune’s eccentricity is also unusually low (e~0.009). While posing somewhat of a puzzle, this observation can be used to constrain new physics whose resulting gravitational perturbations could impart a “kick” to Neptune, resulting in an “eccentricity excitation” Δe which would exceed its observed low eccentricity.

In this week’s paper, Siraj and Loeb use the argument outlined above to constrain primordial black holes (PBHs) with masses in the range between ~10^-7 and ~10^-2 M☉. The resulting constraints are shown in the left panel below, with the corresponding constraints on the fraction of the DM density carried by PBHs, f_PBH, as a function of PBH mass. This is a region of PBH mass already probed by microlensing surveys, but the constraints obtained in this week’s paper are stronger by up to 2 orders of magnitude compared to the existing microlensing ones, restricting PBHs to making up no more than 1/10000th of the total DM density. Note that Siraj and Loeb assume a change in eccentricity due to a single closest encounter rather than a collection of encounters, which in the latter case would be smaller (and therefore likely leading to weaker constraints). The same argument can of course be used beyond PBHs, to constrain the density of rogue unbound interstellar planets with mass in a range a couple of orders of magnitude smaller and larger than Earth’s mass, as shown in the right panel below. These are essentially nomad, free-floating planets, which might in principle have a role to play in explaining Neptune’s observed low eccentricity. Finally, for anybody interested in PBHs, Bradley Kavanagh’s code PBHbounds code on Github might be of interest - this has been used to produce Fig. 1, but I know that beyond this week’s paper, many other researchers who are working on PBHs are using it to conveniently plot constraints on PBHs in a wide range of masses.

Credits: Siraj & Loeb, arXiv:2104.07672

Addendum: this week’s paper is somewhat related to the earlier 2103.04995 by Siraj & Loeb, which I covered in my 2021 Week 10 post, where a similar argument was applied to the eccentricities of the kernel population of the cold population of Kuiper belt objects. However, the preprint was later retracted as the “KBO limit had to be modified to the diffusion regime which weakened significantly the constraints” (the acknowledgements of this week’s paper might or might not be related to this).